Few films capture the golden age studio system firing on all cylinders quite like San Francisco (1936). Directed by W.S. Van Dyke and produced by MGM, the film manages to blend high melodrama, romance, musical grandeur, and one of the most thrilling disaster sequences ever captured on early celluloid. But at the heart of the spectacle, beneath the rumble of collapsing buildings and the glimmer of Art Deco sets, is Jeanette MacDonald — luminous, dignified, and utterly unforgettable.

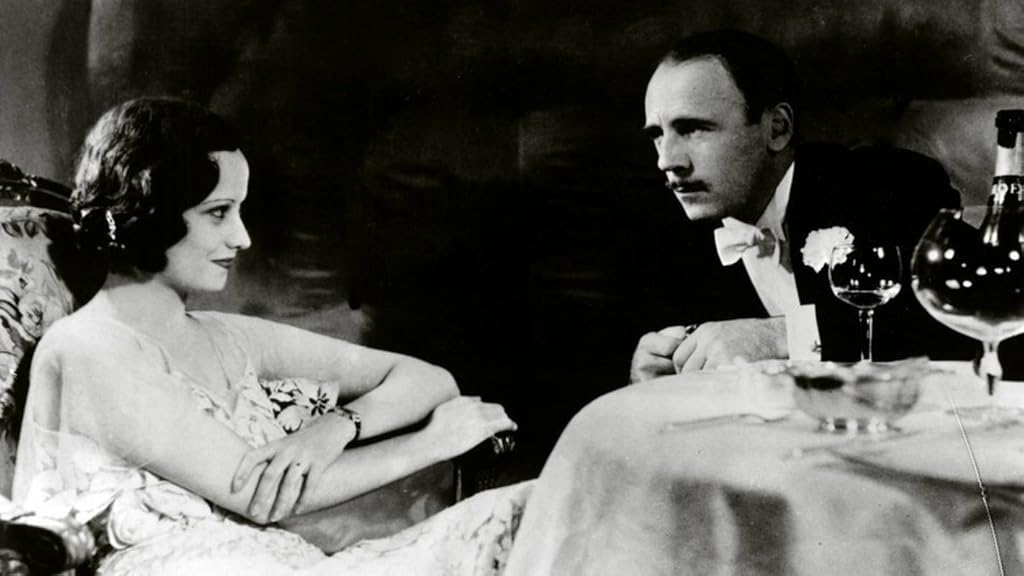

Set in 1906, the story follows Blackie Norton (Clark Gable), a rough-edged saloon owner with political ambitions and a cynical view of religion, and Mary Blake (Jeanette MacDonald), a classically trained singer who arrives in San Francisco looking for work. Their love story unfolds amid the tension between worldly ambition and spiritual redemption, culminating in the cataclysmic real life earthquake that leveled much of the city.

Although the film boasts Gable’s star power and Spencer Tracy’s grounded, Oscar nominated turn as Father Tim Mullin, it’s MacDonald who gives the film its transcendent heart. As Mary Blake, she glides between worlds. First, from the glitzy but morally hazy Paradise Club, then to the hallowed halls of the San Francisco Opera House. MacDonald’s role bridges not just class and ambition but emotional extremes: joy, faith, fear, and ultimately hope.

Her performances of operatic arias and sacred hymns feel startlingly sincere. When she sings “Ave Maria” in the final act, amid a cathedral of rubble and survivors, the moment becomes a cinematic benediction — a symbol of resilience and grace. Photoplay magazine at the time remarked, “Jeanette MacDonald does not just sing — she uplifts. Her voice becomes the spirit of San Francisco itself: wounded but proud.”

MGM spared no expense in showcasing her talents, and rightly so. Her vocal performances — selections from Faust, La Traviata, and the title anthem “San Francisco” — cast the film in a majestic light, reminiscent of grand opera. In a time when musicals often veered toward frivolity, MacDonald brought a rich sense of dignity to the genre.

A Landmark in early disaster cinema, San Francisco was ahead of its time. The earthquake sequence remains stunning even by modern standards, utilizing miniatures, full-scale sets, clever editing, and sound design to evoke the chaos and horror of the 1906 quake. The crumbling streets, the walls that ripple like paper, and the rising smoke all form a montage of terror and beauty.

While San Francisco is often remembered for its musical performances and disaster spectacle, the film is surprisingly rich in its exploration of morality. The contrast between Gable’s hardened cynic and Tracy’s devout priest brings a philosophical weight to the drama. Mary Blake becomes the spiritual pivot. She’s not merely a love interest, but a moral compass.

This, too, is a credit to MacDonald, whose performance never wavers into sentimentality. She brings a classical restraint that amplifies the sincerity of her character’s beliefs. As Father Tim says in the film, “A voice like hers belongs to something higher,” and the film makes you believe it.

San Francisco was a massive hit in 1936, becoming one of the highest grossing films of the year and earning six Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture. Its title song became so popular that it was adopted unofficially as the city’s anthem. It remains a showcase of all the strengths of 1930s Hollywood: big stars, sweeping drama, technical innovation and above all, unforgettable performances.

If Clark Gable is the film’s energy and Spencer Tracy its conscience, Jeanette MacDonald is its soul.